Divisive study finds link between fluoride and childhood IQ loss

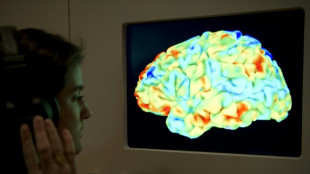

A controversial new study out Monday in a US medical journal could reignite debate over fluoride's safety in water, linking higher exposure levels to lower IQ in children.

Published in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Pediatrics, it has sparked pushback from some scientists who criticize the study's methods, defend the mineral's proven dental benefits, and warn the findings may not directly apply to typical US water fluoridation levels.

Its release comes as President-elect Donald Trump prepares to take office. His health secretary nominee, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is a vocal critic of fluoridated water, which currently serves over 200 million Americans, or nearly two-thirds of the population.

Researchers from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) reviewed 74 studies on fluoride exposure and children's IQ conducted in 10 countries including Canada, China, and India.

The same scientists helped formulate an official government recommendation in August that there is "moderate confidence" that higher levels of fluoride are linked to lower IQ scores.

Now, the team led by Kyla Taylor told AFP the new analysis found a "statistically significant association" between fluoride exposure and reduced IQ scores.

Specifically, the study estimates that for every 1 milligram per liter increase in urinary fluoride -- a marker of overall exposure -- children's IQ drops by 1.63 points.

- Study limitations-

Fluoride's neurotoxicity at high doses is well known, but the controversy lies in the study's suggestion that exposure below 1.5 milligrams per liter -- currently the World Health Organization's safety limit -- may also affect children's IQ.

Crucially, the paper does not clarify how much lower than 1.5 mg/L could be dangerous, leaving questions about whether the US guideline of 0.7 mg/L needs adjustment.

The authors acknowledged that "there were not enough data to determine if 0.7 mg/L of fluoride exposure in drinking water affected children's IQ."

Steven Levy, a member of the national fluoride committee for the American Dental Association, raised significant concerns about the study's methodology.

He pointed out that 52 of the 74 studies reviewed were rated "low quality" by the authors themselves but were still included in the analysis.

"Almost all of the studies have been done in other settings where there are other contaminants, other things we call confounding factors," he told AFP, citing coal pollution in China as an example.

Levy also questioned the study's use of single-point urine samples instead of 24-hour collections, which provide greater accuracy, as well as the challenges in reliably assessing young children's IQ.

With so many uncertainties, Levy argued in an editorial accompanying the study that current policies "should not be affected by the study findings."

The journal also published an editorial commending the study for its methodological rigor.

- Balancing gains against risks -

On the other side of the debate, the benefits of water fluoridation are well documented.

Introduced in the United States in 1945, it quickly reduced cavities in children and tooth loss in adults, earning recognition from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century.

Fluoride, which also occurs naturally in varying levels, helps restore minerals lost to acid breakdown in teeth, reduces acid production by cavity-causing bacteria, and makes it harder for these bacteria to stick to the teeth.

However, with fluoride toothpastes widely available since the 1960s, some research suggests diminishing returns.

Proponents argue fluoridation reduces socioeconomic disparities in dental care, while critics warn it may pose greater risks of neurological harm to vulnerable communities.

"Evidence on the effects of adjusting levels of fluoride or interrupting community water fluoridation programs is critically needed, especially within the context of the US," Fernando Hugo, Chair of the NYU College of Dentistry, told AFP.

P.Ortiz--RTC